by Keith Hickman, Executive Director of Collective Impact, IIRP Graduate School

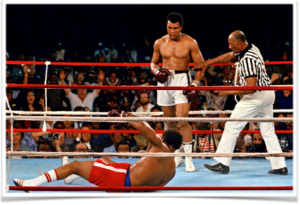

On October 30, 1974, the sports world was turned on its head, when a 32 year-old former heavyweight boxing champion from my hometown in Louisville, KY, regained his title as a major underdog in Kinshasa, Zaire. Muhammad Ali’s defeat of a younger and seemingly invincible George Foreman was a defining moment in my life as an 8 year-old Black kid in search of belonging in a segregated city. It was during the post-fight interview, among the cheers and chants of “Ali Bomaye”, when his powerful words defined belonging for me and many other Black Louisvillians that evening. He looked directly into the camera, shook his finger and said “hello to all my friends in Louisville, KY…where I started.” Oh my, I thought, did he just say Louisville, and call me a friend? He continued, “my greatness started in Louisville, KY.” What, did he just say Louisville was great, that I was great? Then he shouted into the mic in a chanting rhythm, “Louisville, KY is one of the greatest cities in America…Louisville is the greatest, Louisville is the greatest, Louisville is the greatest.” With mouth agape, I knew then, I was somebody, I belonged, because the “People’s Champ” had made that clear to me and to the world. You see, Ali did that for us by simply remembering his roots in Louisville, where his greatness came from, where he belonged, and where he would return after his passing in 2016.

A sense of belonging is a strong connection to family, community/neighborhood, and school. Dr. Karyn Hall, Founder/Director DBT Center of Houston, in the March 24, 2014 issue of Psychology Today, views belonging as “a human need, just like the need for food and shelter.” For Black and Brown students, it is critical, because “feeling that you belong is most important in seeing value in life and in coping with intensely painful emotions”, a key point made by Dr. Hall.

My journey, like many BIPOC students across this country, is a story of reclaiming human dignity and belonging. Growing up the youngest of ten, during the height of court-ordered school integration or busing, was a terrifying moment as a child that still makes me uneasy to this day. This is when I remember becoming aware of how racial identity and racial politics were going to play a role in my educational journey. Therefore, I needed an out, another option, to stop this thing called “busing” that was taking me away from my community and my neighborhood friends. The thought of starting middle school by hopping on a bus, something that I had never done before, riding it to some unknown place, and then fitting in, was scary to say the least, especially given the violent racist reactions and resistance that I witnessed on local television to Black children being bused to mostly “white schools”. Shouts of the “N-Word”, the turning over of school buses, and the vitriol being spewed for us to “go home”, from the mouths of white parents and white students, was quite traumatic. My response, my first act of protest, was to resist in the best way I knew how and make the case to my parents for an alternative solution.

To my luck and surprise, the J. Graham Brown School, the first “magnet school” in the Jefferson County Public School District (JCPS) in Louisville, had recently opened. The genius behind the school was founder Martha Ellison, a visionary and early restorative practitioner, who believed,

“We do not claim to be better than any other school, but our informal, less authoritarian, open environment, combined with the degrees of emphasis on the arts, diversity and the community, combine to create a visible, observable difference and to provide another option for Jefferson County student and parents.”

Now, that was a school I could happily skip to. There, my roots of belonging were nurtured by educators that were courageous and caring and not threatened by my Blackness. So why is creating a structure of belonging beyond hope so important? Because hope requires action.

Structuring Belonging

The amazing Peter Block, American author, consultant, and community builder, powerfully reminds us that,

“We are a community of possibilities, not a community of problems. Community exists for the sake of belonging and takes its identity from the gifts, generosity, and accountability of its citizens.”

In fact, our youngest citizens, that walk in and out of school doors every day, are truly seeking the gifts adults have to offer. If the invitation is genuine and meaningful, then the student gift in return is authenticity of self and community. Therefore, students need to be accepted for who they are, both problems and promises, and their potential nurtured by every caring adult on staff, thus opening up the possibilities that await them. A structure of belonging can’t exist when students are segregated, isolated and marginalized, which often occurs when adults use their authority ungracefully and punitively.

In recent studies by the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, 2019 and the Search Institutes report on Insights & Evidence: The Intersection of Developmental Relationships, Equitable Environments, and SEL, 2020, organizations and schools that fully integrate SEL in everything they do, achieve the full promise and outcomes of the methods. The critical variable, they show, is relationship. In fact, student transformation is likely to occur as these relationships develop within the context of diversity, equity, and inclusion. And report after report points to the fact that student connection and belonging are strong indicators of academic, social, emotional and post-secondary success. We know from the extensive research from Healthy People 2030, that health and mortality are associated with levels of education. As that report states,

“Children who routinely experience forms of social discrimination — like bullying — are more likely to struggle with math and reading. They’re also less likely to graduate from high school or go to college. This means they’re less likely to get safe, high-paying jobs and more likely to have health problems like heart disease, diabetes, and depression.”

I return back to my own experience at the J. Graham Brown School, the only school in the State of Kentucky where kindergartners and seniors learn together under one roof —this is belonging and connection! Where cross-age mentoring and learning opportunities are inter-generational – this is belonging and connection! Where self-directed learning is student voice and agency – this is belonging and connection! And inclusivity and celebration of diversity is the demographic and reality – simply put, belonging and connection!

Equity is Belonging

You can’t build equity without students belonging and being connected to their schools. This requires a systemic and intentional approach to create learning environments that are multimodal. For example, recently the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and the IIRP Graduate School, co-wrote a white paper supporting aligning restorative practices and social and emotional learning to improve school climate by strengthening relationships throughout the school building.

There are five areas that schools must target in their whole-school approach:

1. Align RP and SEL under a single initiative.

2. Integrate preventive practices into all aspects of daily life in the school.

3. Establish restorative responses to behavior that promote SEL.

4. Strengthen staff skills and mindsets that mutually reinforce RP and SEL so they can model practices and support students.

5. Involve students, families, and community partners in SEL and RP initiatives.

Aligned, these two evidenced-based approaches share common characteristics for inclusive and welcoming environments, healthy relationships for all students, long-term academic success and social-emotional well-being, and reaching equitable opportunities and outcomes. These common characteristics were definitely elements throughout my K-12 experience.

I feel fortunate that the Brown School created a space for me to belong during one of the most traumatic times of my childhood; that I learned early on from caring adults what social, emotional and cultural connection meant – and that I had a hero, the “People’s Champ”, that looked me in the eyes from the continent of Africa and proclaimed that day in 1974 that I was great and that “Louisville, KY is the greatest city in America.”

Keith Hickman is the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP) Executive Director of Collective Impact. In this role, he works with partner organizations, both domestically and globally, to pursue the IIRP mission of positively impacting social health. He served as an advisor to the Maryland Commission on the School-to-Prison Pipeline and Restorative Practices, is a partner scholar on the CASEL Equity Work Group, and is a member of the Research Development and Design Team for the California Safe, Healthy, Responsive Schools Network. Keith and IIRP are valued partners and collaborators with Community Matters.

Keith Hickman is the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP) Executive Director of Collective Impact. In this role, he works with partner organizations, both domestically and globally, to pursue the IIRP mission of positively impacting social health. He served as an advisor to the Maryland Commission on the School-to-Prison Pipeline and Restorative Practices, is a partner scholar on the CASEL Equity Work Group, and is a member of the Research Development and Design Team for the California Safe, Healthy, Responsive Schools Network. Keith and IIRP are valued partners and collaborators with Community Matters.